CATALYST

DENVER MUSEUM OF NATURE & SCIENCE ONLINE MAGAZINE

What Happened to Lizards When the Dinosaurs Went Extinct?

Turns Out, 66-Million Years Ago, Colorado Was a Really Bad Place for All Sorts of Reptiles

"After Armageddon" from the Ancient Denvers series of paintings, 65 million years ago, Denver Formation. (Illustration/ Denver Museum of Nature & Science)

Sixty-six million years ago a Mount Everest-sized asteroid struck Earth and caused the extinction of the dinosaurs — alongside nearly 75% of life on the planet. This was the single worst day for multicellular life on Earth. Over the past several decades, the Denver Museum of Nature & Science scientists, including myself, have been working east of Denver to build a fossil dataset that spans this extinction event. Recently, Dr. Tyler Lyson and I published a study in the scientific journal Proceedings B where we analyzed the lizard fossils from either side of the extinction event and we can now safely say this was also a terrible day for lizards.

I led the analysis of 20,000 microvertebrate fossils, including 255 lizards, collected from two localities that span the End-Cretaceous extinction. We found that the lizard fauna during the end of the age of the dinosaurs was remarkably diverse with at least 27 different types of lizards from just one locality! Of these species, only three survived the asteroid impact.

The secret to this discovery? Dirt. Lots of dirt.

Field work at West Bijou involves collecting thousands of pounds of sediment that then get washed using specially-constructed box screens. (Photo/ Tyler Lyson)

Over the past two decades, DMNS scientists, volunteers and interns collected several tons of dirt from two localities named “Ian’s Slope” and “Gars Galore,” both located 40 miles east of Denver. The dirt was washed at the Museum and offsite, including the Corral Bluffs Research Center in Colorado Springs, using a special set of box screens. The resulting concentrated sediment was then sorted underneath a microscope to pull out all the small vertebrate fossils, including bits of ancient turtle shell, crocodilian teeth, fish scales and lizard jaws and vertebrae.

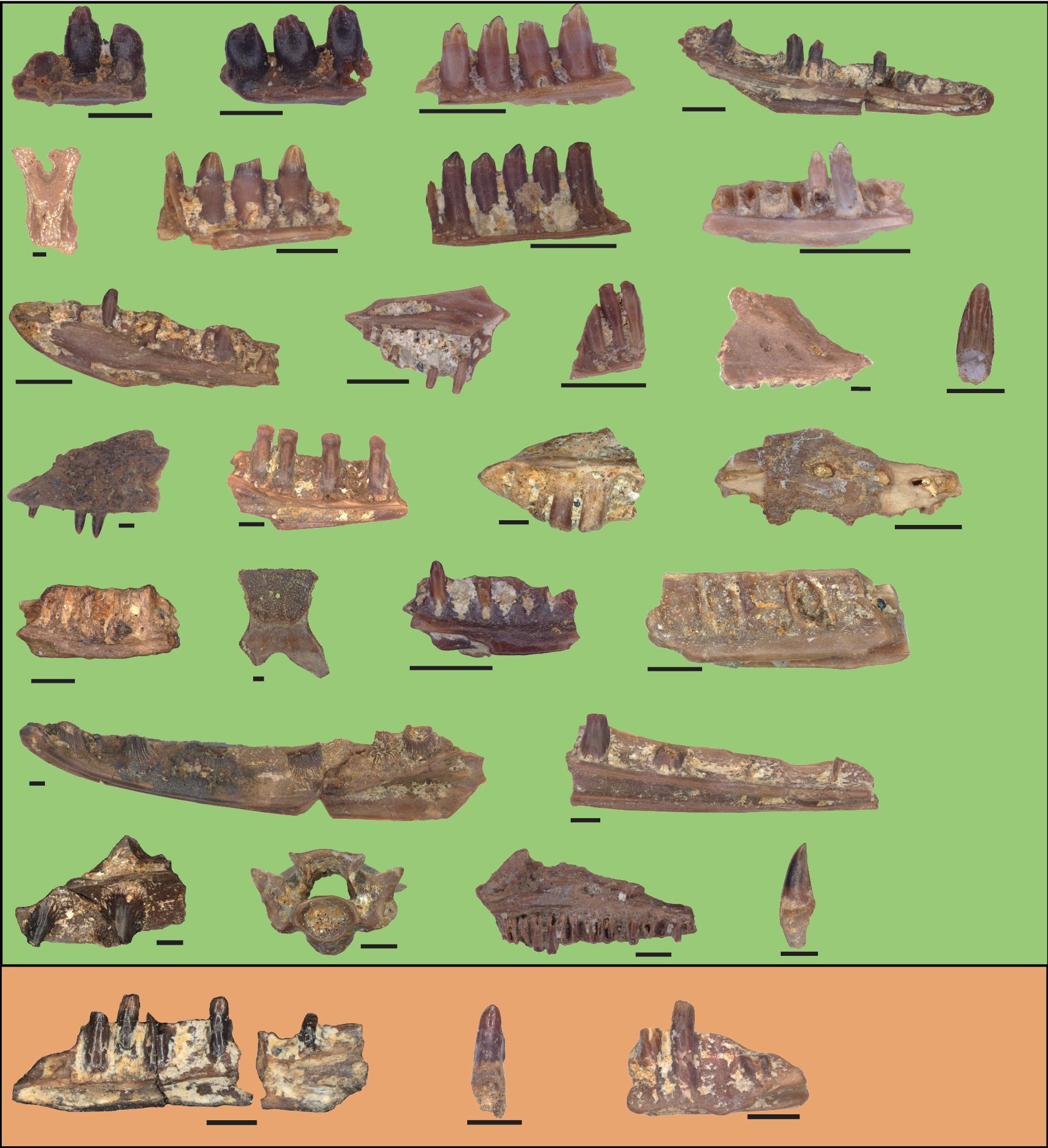

Lizard fossils from before, green background, and after, orange background, the End-Cretaceous mass extinction. The three surviving species represent just 10% of the original diversity. (Photo/ Petermann and Lyson)

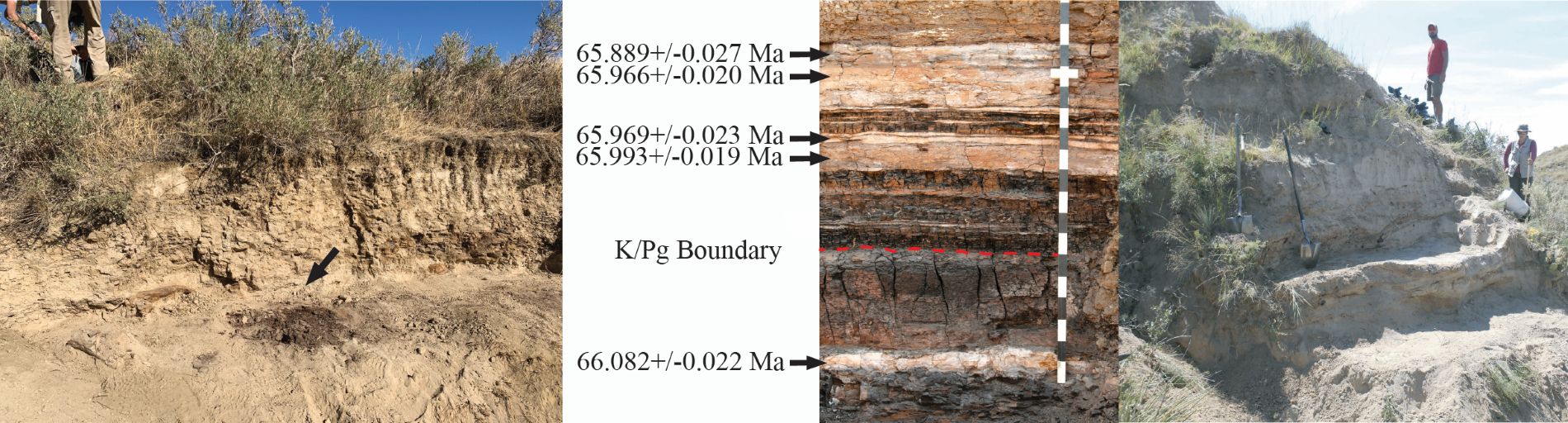

This is an incredibly tedious and time-intensive process that was largely done by volunteers here at the Museum. The fossils from the two localities are incredibly exciting because the Ian’s Slope locality represents a moment in time roughly 57,000 years before the mass extinction and the Gars Galore locality some 128,000 years afterwards. Together, they offer a vivid before-and-after snapshot of Earth’s last mass extinction, providing a fossil record that allows us to compare and contrast life on either side of the event.

From these sites, we learned that during the end of the dinosaur age, lizards in Colorado were exceptionally diverse. The most diverse groups were polyglyphanodontians and anguimorphs — the group that includes glass lizards, Gila monsters and monitor lizards. After the extinction, however, only three lizard species remained — including forms that belong to skinks and a now-extinct type of anguimorph lizard. This change translates into an extinction rate of over 90%, which is much higher than that for comparably sized small vertebrates.

The Late Cretaceous locality, left, produces fossils just 57,000 years before the extinction. Several ashes have been dated from a boundary section, middle, roughly in the middle between both localities which provides an incredibly precise chronological framework for the study. The early Paleocene locality, right, records the diversity roughly 128,000 years after the extinction event. (Photo/ Lyson, Charles Nelson and Rick Wicker.)

Late Cretaceous lizards showed the same feeding specializations as modern lizards and included planteaters, meat-eaters and mostly insect eaters. They vastly ranged in size as well, from small species the size of a fence lizard to large ones the size of a small iguana. After the extinction, the only species that survive are on the smaller side and are either food generalists or insectivores.

“Thanks to our long-term partnership with the Savory Institute who own the land where the fossils were collected, as well as countless hours of work by our volunteers and interns picking through the dirt for the precious vertebrate fossils, we are building some incredible datasets that provide insights on how life responded when the asteroid struck Earth 66 million years ago,” said co-author Dr. Tyler Lyson, senior curator of vertebrate paleontology and principal investigator of the Denver Basin Project.

Read more: Uncovering the Mysteries of Mammals

It’s truly amazing that after nearly disappearing from the face of the planet at the End-Cretaceous extinction event, lizards have since diversified to over 12,000 modern species. This certainly speaks to the resiliency of life on Earth.